Shy Blakeney, co-founder of Recover Integrity, an exclusive extended care treatment community for men, learned about making the world a better place from his parents, grew up Jewish-Jewish, couldn’t hear other people until he sobered up, believes everyone has a soul, was a hip hop emcee, and hates gyms

What’s the story behind your name?

It’s a Hebrew name, Yeshaia. The [Ashkenazi] tradition is to be named after a relative who passed away. The root of the word means salvation. It epitomizes the idea that we can craft the world into a better place. My parents dedicated most of their lives to that.

Where and who do you come from?

I was born in Alta Bates, Berkeley, California. I was the youngest of three. I have two older sisters. My father is African-American. My mother is Jewish. They’ve been married for 50 years.

My mother came from a middle class family, which eventually became an upper class family. She came from Perth Amboy, New Jersey. My grandfather was a really hardworking, conscientious man who eventually came out to California and worked at a little place called Pick and Save, which was a warehouse on Sepulveda at the time. He became the CEO and it eventually became Big Lots. My grandfather was the lay cantor and one of the founders of Temple Akiba, which is also on Sepulveda. He married my grandmother, Betty, who I think he kissed in a game of spin the bottle when they were 12 and 13 years old; he’s 90-something now, and they were together the whole time.

My father came from poverty. My dad was born in Central Valley, California, in a little town called Hanford. He has 13 brothers and sisters. They grew up in a one-bedroom shack that his father had built in a segregated agricultural town. You started working when you were six years old. They couldn’t afford shoes. I wrote a report on it when I was in high school. My history teacher said, “I think you’re confused. This is not the history of California.” I said, “I think you’re confused. It is.”

My parents got married in the ’70s. There was always music playing. It was kind of a party house. We usually had relatives living with us. There was lots of celebration.

My parents are baby boomer, revolutionary, Berkeley types.

On the one hand, there were tons of books in my house, deep and rich conversation, alternative ways of child raising. There was also dysfunction in my house. My father was an alcoholic.

There was no pressure to achieve or make money in my house or even go to college. Even though my parents had a strong academic resume, they didn’t do it to be academics. They did it because they wanted to learn how to affect change.

They graduated from Harvard and the government was trying to pass a bill in California that said if the father of a child is not present to sign the birth certificate, then the mother is not eligible for welfare. From a progressive point of view, that’s insane, right? From a conservative point of view, they were attempting to get fathers to show up. My parents disagreed vehemently. They brought buses of pregnant women up to the capitol in Sacramento and marched them in as they were trying to pass this bill. Squashed it. It didn’t pass. They got a call from Governor Reagan‘s office saying, “Do you want to come work for us?”

My father said, “Yes.” My mother said, “Fuck the man.” My dad looked at her and said,

“Better to be at the table than to throw rocks at the window.”

So, they started working for Governor Reagan on welfare issues. When he became president, he brought them in and they worked on welfare reform. They did that on the side.

Their primary work was running mental health treatment programs for inner city girls. They ran them as therapeutic communities, not lockdown psychiatric wards. They had three of them in Berkeley. They did it with no medication. They were wildly successful.

What role did Judaism play in your upbringing?

I went to Jewish school. I went to temple. I was bar mitzvah‘ed. We celebrated all the Jewish holidays, no Christmas trees.

We were Jewish-Jewish.

I grew up surrounded by Judaism. It had a huge impact on me culturally, because it was my environment. It wasn’t a question whether I was going to have a bar mitzvah, it was a given. In terms of God and spirituality, there were no thoughts about any of that as a kid. I was an atheist by the time I was 11.

Tooth Fairy, Santa Claus, God, you know.

I didn’t consider being actively Jewish again until my 20s.

My spiritual journey started when I was 11, around the same time I became an atheist. I was always very curious. I had a moment where I was able to conceive of death without the filters of the ego. It became clear that I was going to die and that nobody could do anything about it. Actually, everybody would die, and nobody ever talked about it. It was like a panic attack. I became pretty philosophical.

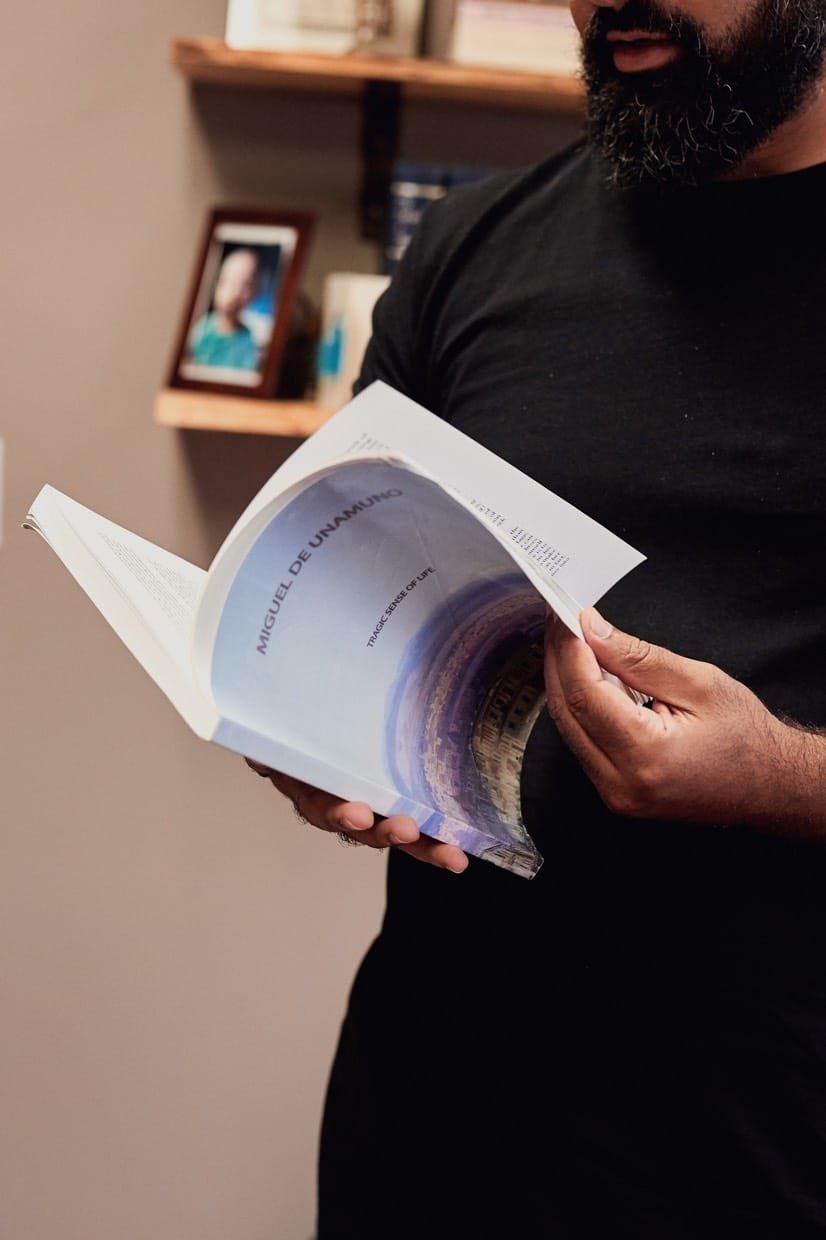

One of the first books I read when I was a kid that I thought was really fascinating was The Dancing Wu Li Masters. It was by Gary Zukav, an Eastern religious philosopher. He was talking about the nature of reality from an Eastern spiritual perspective, and it blew my mind.

The turning point in Judaism came completely accidentally. My father hit bottom. He chose a Jewish rehab. He was there for six months and I used to visit him. On Shabbos, they had a big service and a dinner. I would always be smoking weed on Friday night. I think I was 19.

I put my Visine in, ate a mint, and I went to this rehab service.

I tried to show up late, so I would just get the chicken. I didn’t want the service. I did that almost every week.

Then, I got busted for trafficking marijuana in 2003. I had known that this rehab did alternative sentencing. I didn’t want to go to prison, and I was facing four years. I went to rehab just to not go to prison. I was on autopilot from 12 or 13 to 21. I wasn’t learning. I was just smoking weed, and running around, and getting in fights, and partying. A little lightweight crime. Kind of a street punk.

I was unreflective. I could not hear other people.

I go to this rehab, Beit T’Shuvah, and sober up, and through dialoguing and connection, I realized, “I don’t know how to live life. What the fuck am I doing?” I woke up. I started to learn. I was in an environment with a lot of wise people. In that environment was Torah study, and Shabbat, and a rabbi who made Judaism accessible to me. His name was Mark Borovitz. It was about drawing what you could from Judaism to build a foundation for how you wanted to live.

Then, Rabbi Heschel built a bridge for me to be able to take Judaism seriously, as its own truth.

Heschel touched my soul.

When I would read him, he would awaken my spirit. William James talked about religious feelings. I’d read him, and I’d be filled with religious feeling. I was a counselor there for a long time. The rabbi asked if I was interested in taking his spot as the head rabbi. I said yes. He went out of town and I ran a service. Then, I went to rabbinical school.

How do you think Judaism and your recovery are intertwined?

The concepts of recovery are in Judaism.

A ba’al teshuva returns to a path, recovers, and repents. It’s the paradigm that we all need. I think that our whole society is disconnecting from their souls and each other in scary and rapid ways. I like to ask, “Is there a you in there?” Something that you don’t necessarily identify only as your body, your brain. “Is there a you, a spirit, a will, a soul?”

Almost everybody says, “Yes,” if they’re honest. If you don’t think there’s a you, then what are we hanging out for? I think the concept that’s very universal, that can transcend our cultural and historical differences and roots, genders, sexual orientations, is this idea that we all have a soul and we all need recovery. That connects very much to Judaism, or any religion, for that matter.

When you were younger, what did you want to become?

I was a hip hop emcee. I still am, but I was pursuing hip hop as a career for 20 years.

Tupac was my hero, my James Dean, my rebel. But, he had a cause. He encapsulated what it feels like to be a passionate, raging, non-filtered young black man. I grew up on gangsta rap. It was Tupac, it was Dr. Dre, it was Mac Mall, 3X Krazy.

I moved to LA and was hanging out with the taggers and the rappers and weed smokers. A guy across the street named Deuce brings over a stack of CDs, the history of East Coast rap. He put me on hip hop.

I started thinking, “What am I trying to say?” Gangster rap is the toughest. It’s women and money. Hip hop was much more conscious. You could express yourself as an individual as opposed to part of a larger gang. Then, I became an emcee.

Emceeing allowed me to develop what I wanted to talk about: justice, depth, poetry, art, and love. A little swagger.

I set up a studio when I was in rehab and started recording. I performed all over LA. I was doing that at night and drug counseling during the day. I had a kid when I was 23 and got married. By the time I was 27, I was managing the band, working full-time, and I had a couple of kids. I wondered, “How are you going to take care of these kids?” I stopped pursuing emceeing as a career when I was 28 but continued to do hip hop.

I’m working on a non-corny Jewish hip hop album.

It’s called Post Judaeo, and it’s about the death and rebirth of Judaism.

What advice would you give your teenage self?

Find one mentor and trust them. Period.

I did life on my own. I mentor a lot of 15, 16, 17 year olds. Some successfully, where we’re able to change the trajectory before you get too lost. Some, not. They got to go through what they got to go through. If I had been able to connect with somebody I could emulate and look up to and who was there for me, that would have been a good mentor and a teacher.

What are you working on right now?

I was the kid who didn’t do homework. I watched Spiderman and avoided responsibility, because responsibility is dull and painful.

Then, I got sober. I’ve had to recover and reclaim those tasks that I tried to avoid. Everything from making your bed to doing laundry and checking the bills. I just recently picked up a prayer practice in the morning, which has been profound. I broke down in tears my third time doing it. I started biking. Exercise has always been challenging for me.

I hate gyms, I think they’re horrible torture chambers.

I had anxiety this year. It hasn’t happened in eight years. It was like, “Hey, you got to shift.” Anxiety is a fantastic motivator to change. You start to say, “I need to exercise” or “I need to pray” or “I need to look at the structure of my life.”

When do you feel like the best version of yourself?

On stage, when I was performing. I really like being in studios. I really like making music.

I’ll tell you the best I felt in the last few weeks: I took my oldest daughter to the studio. To see her be a kid and dance around and make music and be comfortable in the studio. Watching her, I was thinking, “God weaves wonderful moments.”

Definitely in counseling when you connect with somebody. I love teaching. I also love learning. I do that with my rabbi.

Do you have a personal mantra?

I’m the worst case scenario guy. I have to tell myself, “We’re all going to end or go away. Don’t worry about it.”

It makes me not take life too seriously, which I find quite helpful.

“Patience and compassion with yourself” emerged from my spirit three or four years ago. I’d gone back to school, and I was studying statistics, and math was really hard for me. I love to learn, but I came to realize that one of the things about intelligence is the ability to have fun with problems, as opposed to trying to solve them. When you get frustrated, at least for me, it can be part of the process of learning.

What are some of your most prized possessions?

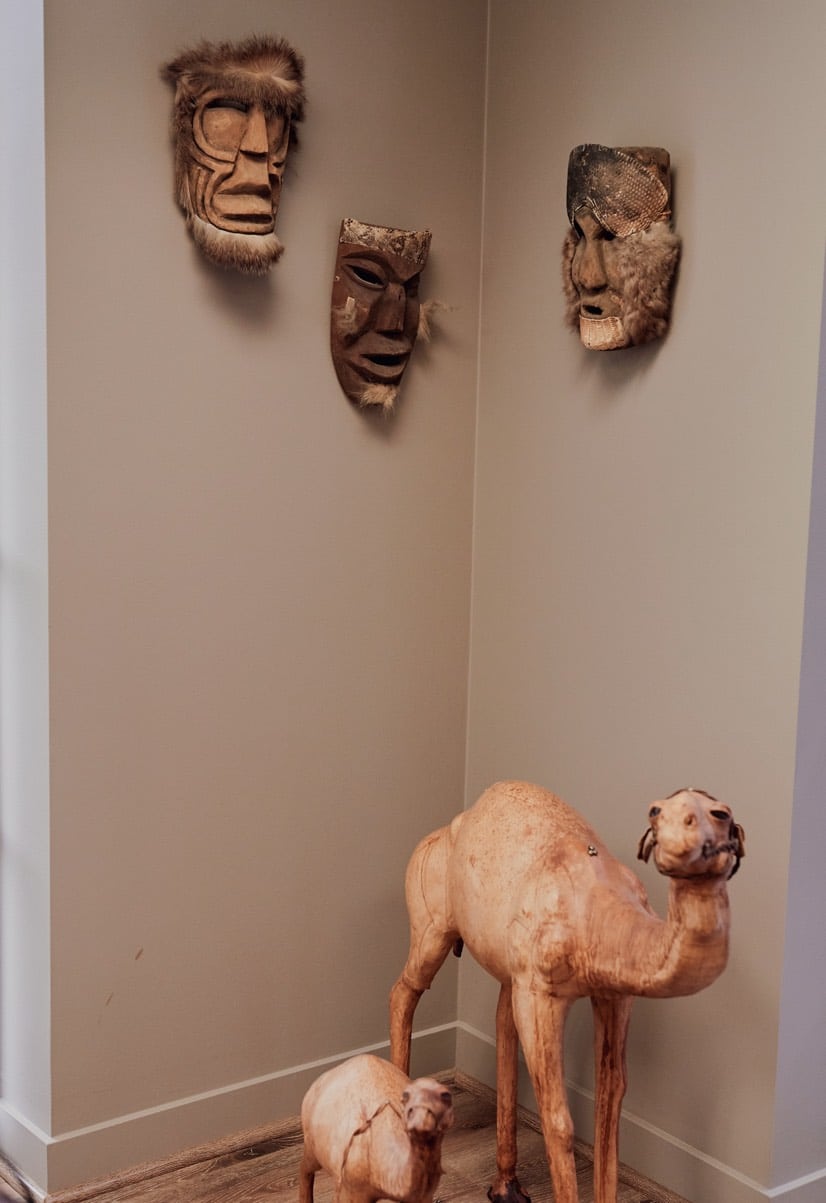

Anything that matters to me is probably in my office.

There are old prints from biblical scenes. One is the death of the firstborn with Pharaoh. Another is Moses with Egypt in the background. One is of Aaron, the high priest. I study the Bible, so I picked the ones that spoke to me. I like Moses. I named my son after him. He was a perfectly flawed character.

I have a not-so-little Komodo dragon statue. I named her Addiction. A Komodo dragon will bite much larger prey and then follow it around for three days. They have bacteria in their mouth that eventually kills their prey. In the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous, it says that, “Addiction is cunning, baffling, and powerful.” One of the things that I’m teaching about addiction is that the first issue with people who are trying to understand what’s going on, whether it’s the clients or the families, is that they underestimate the problem. So, I thought that was a decent metaphor.

Photos by Marissa Alves. Edited by Sarah Colborne.

Thank you for visiting Arq!

Arq is no longer publishing new content. We hope you'll enjoy our archived posts.