Writer Chris Kraus lives in a tucked-away, perched-on-a-hilltop, peaceful community smack in the middle of Los Angeles, a city that’s increasingly reminding her of the New York City she fled for something kinder years ago. She told us about her multi-national upbringing, the moment when she found out she was Jewish, how writing has made her more empathetic, why she’s no longer afraid of ending up in a dumpster, and much more.

What is your earliest memory?

It’s in the Bronx, in the apartment building where we lived. Seeing a praying mantis in some of the brush that grew in the alleyway between buildings and my mother telling me that it was completely illegal to kill a praying mantis and you’d go to prison for the rest of your life.

I was really afraid to touch it. I guess that was the desired effect.

Is there a story behind your name?

I was originally Christine. When I left New Zealand and moved to New York, I just called myself Chris. Kraus, that’s my father’s name. As far as I know, it’s Czechoslovakian Jewish.

My mother is not Jewish, so I am not technically Jewish. However, my mother was a lot more Jewish than my father. Culturally, humanistically, her accent, the expressions that she would use. My mother was such a social person. She also had a great sense of social justice and empathy and concern for other people.

My father was extremely intelligent, more of a hermit. Before we emigrated to New Zealand, my father would come home with the The New York Review of Books and The Village Voice, and piles and piles of books. He taught me to read when I was 3.

Where did you grow up?

Born in the Bronx. My family got out when I was 5 and lived in Milford, Connecticut. We lived right on the other side of Burwell Beach, this exclusive beach community.

We were always looking over to the other side. Story of my life.

My parents emigrated to New Zealand when I was 14. I went to university there. I have a lot of friends and connections to New Zealand, but I left in ’77. I thought I would move to London, but it didn’t work out. I still had a U.S. passport, so I went to New York.

How did living in all of those places form your identity?

The move to New Zealand was the most radical.

Have you ever read “O Pioneers!” by Willa Cather? It’s a wonderful book. Her parents moved from a Midwestern town to a very wild and raw place in Nebraska when she was 8 years old. This was, of course, more pronounced before social media and 24/7 connectivity. Up until that point, the world had been only what you see, and you didn’t really imagine that things could be so radically different somewhere else.

To go from that hated suburb of Milford to – boom! – New Zealand, 10,000 miles away, that was shocking, and, then, energizing. Such an awakening to move there.

Part of my decision to not stay forever was because I had this precocious career in journalism. By the time I was 21, I’d been working as a journalist for 5 years already. I had a really good job, a nice apartment, nice clothes, and, I thought, “Well, is this what my life is going to be when I’m 40?” I really wanted to be an artist, so, I went to New York, and, instead, really suffered.

How would you describe your younger self?

Wanting to stick up for people. I experience other people’s unhappiness in a very tangible and physical way. The pain of that made me really want to do things to alleviate it. I was very political.

When we moved to New Zealand, the Vietnam War wasn’t over yet. I was really involved in the Anti-Apartheid Movement, very involved in end of the war stuff, tenants’ rights, things to do with the environment and nuclear issues.

What advice would you give your teenage self?

Don’t give up.

It’s so easy to get sidetracked. By the time you’re 25, there are all these pressures on you to have a career, to have a better apartment, to have an appropriate partner. The ideals of your adolescence can be left behind in the dust.

I was able to maintain my adolescence for a very long time, probably into late middle age, by basing my life around the things that are most important to me: writing, art, literature, culture, communicating. That’s the channel that I work through: culture.

In another life, I would like to be a politician.

I would like to run for local office. In this life, I’m a writer.

Describe what you do and how your career has evolved.

It’s very simple, I’m a writer.

In other times in history, it was very common and ordinary that a writer might also be an editor of an imprint, and write criticism, and teach.

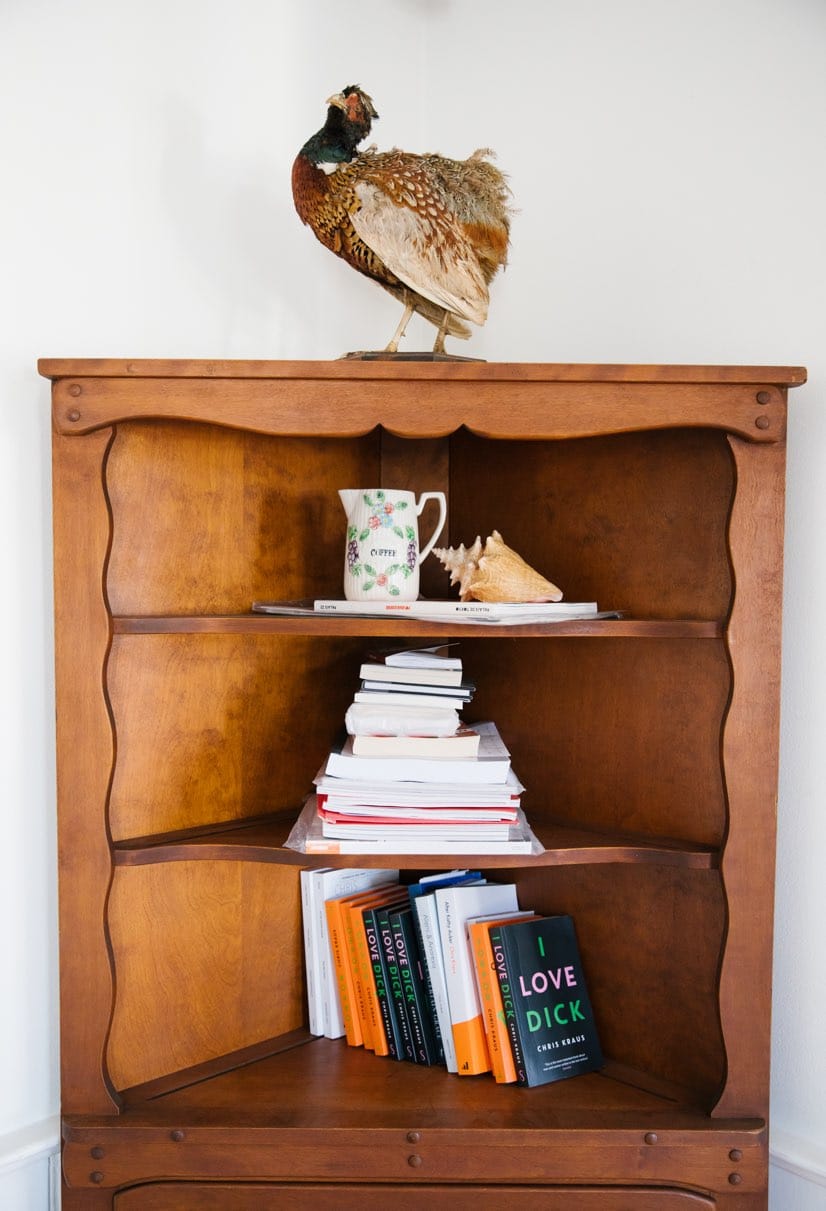

I didn’t start writing seriously until 1997 with “I Love Dick.” I postponed writing for years and years, first by studying acting when I got to New York, then by making films. Then, I was married to Sylvère Lotringer, who was a tenured professor at Columbia, and his family was in France, and he accepted a lot of invitations, so we were moving around a lot. That made it difficult for me to get going on my own.

Also, because we couldn’t really afford to live in New York at one point, we were living upstate. I was kind of exiled up there in the Southern Adirondacks, but I got involved in doing videos with elementary school kids. One of my films, Traveling at Night, is about the Underground Railroad.

It’s about the impossibility of knowing anything in history.

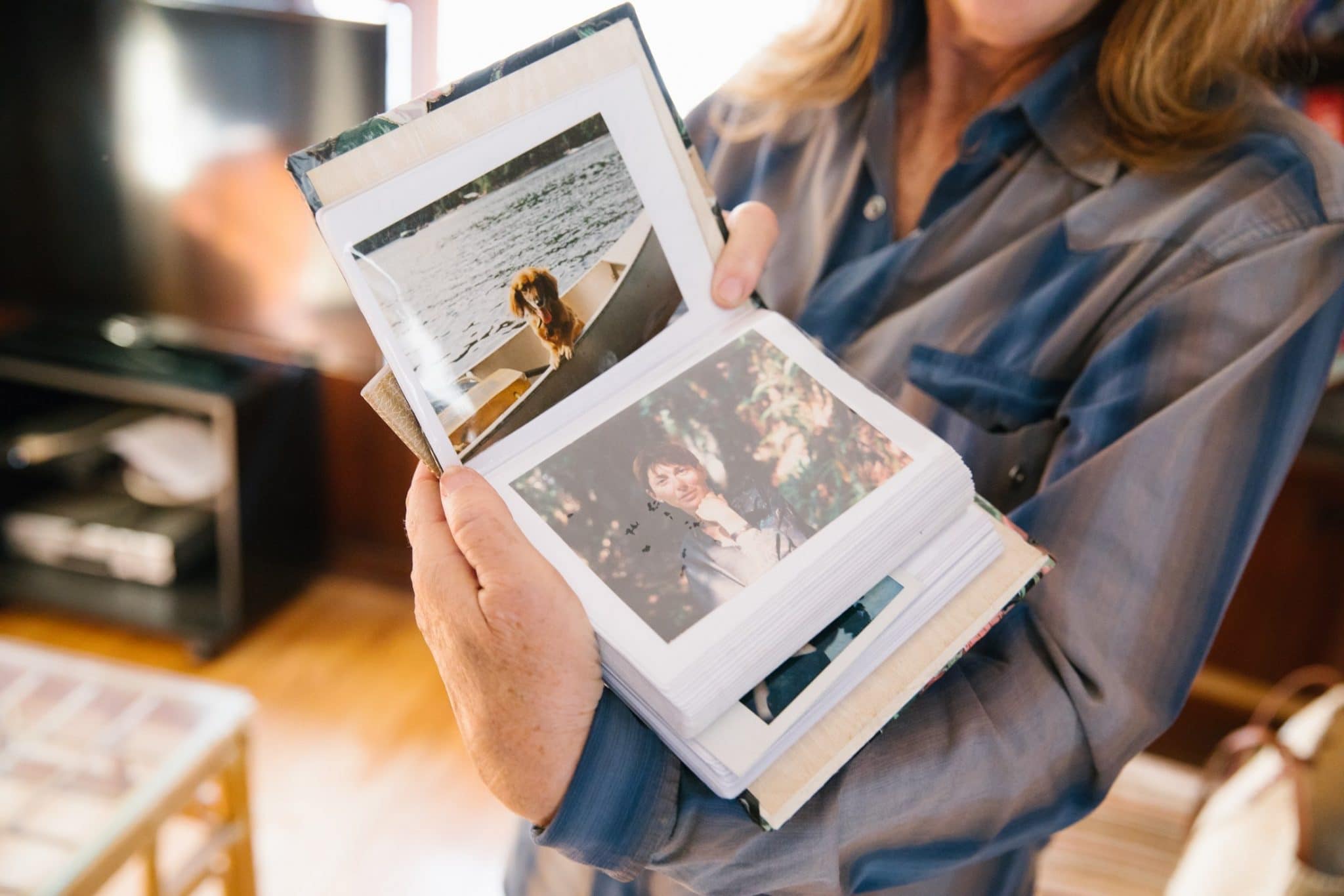

That’s an idea that I would pick up later for the Acker biography: how incredibly unreliable memory and facts are. Who knows if the Underground Railroad existed there or not? They’d like to think so, but, unlike Vermont, where there were a lot more educated and organized people, nothing was written down.

Even in my exile, I managed to find something to get interested in, but it did impede having a more conventional art or literary career. Sylvère said to me, “Someday, you’ll look back on these years as a time when you really had a fallow and peaceful time, and you won’t regret it.” And he was right.

Your parents didn’t tell you about your Jewish background until you were an adult. Why was that and did spirituality or religion play a role in your upbringing?

There were some unpleasant things in my father’s family history that made him turn away. He had to leave school when he was 14 to support his mother who had polio. His father had died. There was not a lot of support from the relatives, and I think that hardened him and made him not just turn against those people, but against his whole background.

My parents went to an Episcopalian church. I visited that neighborhood in the Bronx recently, and it is still like an oasis of order and beauty in the midst of a very poor neighborhood. The church sits on this plot with leafy green trees, and it beckons as a more beautiful life.

I don’t know if those spiritual values were all that important to me, the ones at the Episcopal church. It seemed like an aspirational religion. Definitely an Anglophile religion. Also, kind of a smug religion.

There were not a lot of Jews in Milford, Connecticut, but my best friend was one, and not a lot of Jews in Wellington, New Zealand, but I seemed to gravitate to them. When I was 21, I come back to New York and I meet these long lost relatives who were the Glassmans and the Heinemanns. And it’s like, “Oh, we’re Jewish.”

How has your personal connection to Judaism shifted as you’ve gone through life?

I was with Sylvère for decades, and we’re still very close. We do Semiotext(e) together. That was an extreme exposure to Jewish identity, because of his family history. He was a hidden child during the war. Hearing his mother, a remarkable, wonderful person, tell stories about how they fled Poland, and then they were in Paris, and then they had to go into hiding. Being with Sylvère, I inhaled all that.

Then, I did all the work on the philosopher Simone Weil, and, once again, when I moved to New York, most of my friends were Jewish.

I assimilated that secular, humanist, Jewish thing.

As people get older, they tend to drift towards religion. If that happens to me, I might move towards Judaism.

What is a typical day like for you?

If I’m writing, then a typical day is very different than another day. I’d totally clear my schedule, wake up thinking about it, and then piss around and do this and that all morning. Not one of those morning writers. Start working around Noon, and work until 4 or 5. If I’m really into it, come back and work some more at night.

If you don’t have a 9-to-5 job, your house becomes this island.

You could be anywhere. You could be miles up in British Columbia. The house becomes this haven, and whatever you choose to make it, and whoever you invite into it. It’s very free.

How have you seen your work have an impact on your readers?

I’ve just got to say Sheila Heti does that so beautifully. Did you read How Should a Person Be? That is a classic. Isn’t that really the subtitle of every book? Isn’t that the question that everyone is asking themselves all the time? That book helped people ask those questions in their own lives.

I did an event in London for I Love Dick where, instead of talking about it, the writer Joanna Walsh and I decided, “Well, we’ll just solve people’s problems.” People treat it as if it’s a self-help book anyway. So, we had the audience give us questions to answer on stage. There was a polyamorous dilemma, and mostly boyfriend trouble, I gotta say.

We tried to be as sincere as we could in giving the advice, knowing that one could never really advise another person.

The most amazing thing is when, after reading, somebody comes up with your book, and there are 75 post-its sticking out of the book, and all these underlinings. They’ve been reading that book so hard. Obviously that book has meant something to them. It doesn’t get better than that.

When you were writing Kathy Acker’s biography, you really had to put yourself in her shoes and suspend judgment to understand her behavior and choices. What lessons can we all learn from your experience?

You write a biography, you’re collecting all this information, and you’re trying to understand the person. Everything that we do has a logic chain, right? Other people think, “That’s crazy. Why is she doing that?” But, within your logic chain, one thing leads to another and it seems to make sense.

Looking at Kathy, I would see her doing things and think, “Bad choice, Kathy. Why did you do that?” Finally, I realized that her goal was to be a writer. That was her highest goal. She was pretty single minded about that. All of her choices did serve that.

You can’t judge a person according to the criteria that we generally use in this culture: a happy partnership, a pleasant domestic life. That is not necessarily everyone’s criteria for happiness.

She didn’t have those things, and she made choices that almost precluded them. She was going to date somebody, she would invariably pick someone who was married. She meets a group of women who really like and welcome her, she sleeps with their boyfriends. Peace and calm didn’t work for her. Drama worked for her very well, and she wrote her books under those conditions.

I feel as much like a New Zealander or a Canadian at this point as I do an American, and, in those cultures, people in their 20s have a sense of restraint, that you should be calculating the effect of your self-expression on other people. People in America don’t seem to have that chip now. It’s self-expression at any cost, and no sense of stability, and that means no giving the other person the benefit of the doubt. People are so amped up to express themselves that they’re not really taking in the existence of others.

So, be nice.

Do you have a personal mantra?

It’s better than waitressing.

What’s your biggest insecurity or fear?

It used to be ending up in a dumpster, but I realize that’s not likely. I was exaggerating.

Seeing LA change. It’s not the city that I moved to. It’s become more and more like the New York I left, and how many more cities can I hop around to? In the 90’s, LA was so cheap, it was so easy. You’d get a job anytime, you could get a great, cheap apartment or house. No one gave a shit, there was none of this competitive New York stuff. But it’s all come here now, and it’s very intense.

The world is shrinking, and it’s becoming a less mysterious place. That’s my biggest sadness or fear, that all the mystery is drained out of the world.

When do you feel like the best version of yourself or happiest?

Writing, when it goes well, and finishing something and knowing you did the right thing. Touring. Afterwards, feeling like something really connected with the audience, it was a good night. It’s deeply satisfying.

Kayaking and being in the wilderness. You just drink it in. Whenever you’re in a bad place, you can close your eyes and be back there. It’s wonderful. Water, trees, birds.

What has been your proudest moment?

Finishing a book.

It leaves your body. To write the book, it has to be in your body for months or years. You had to carry it around with you for months or years, and it never leaves until you’re finished. When you’ve finished the book, it’s finally left your body, and it’s such a peaceful feeling.

What’s something you’ve learned recently?

I can’t say that I’ve learned anything.

I would like to say I learned how to use the scanner. I tried last night and I failed again. I can scan one page, but I can’t figure out how to scan multiple pages into a single document. I hope to learn that before I die.

What do you admire most in others?

Courage, wit, sparkle, persistence, energy, kindness. Definitely kindness.

What’s the most overrated virtue?

Self-promotion. That’s a positive now. The insecurity that makes people think they have to do it all the time. And meanness. Taking the easy way out because it’s easier to go along with the crowd and be mean to somebody, even if you think it’s wrong.

Do you have a favorite Jewish holiday?

I think Purim is beautiful. I like that it’s Easter, but it’s bigger and more colorful. It’s almost like that Hindu one, where everybody paints themselves in March. Purim is a beautiful holiday, and sheep and lambs come into it. And those are my totem animals.

Why?

Because a sheep keeps its head down. It doesn’t draw a lot of attention to itself, but it gives so much.

Photos by Jennifer Emerling

Thank you for visiting Arq!

Arq is no longer publishing new content. We hope you'll enjoy our archived posts.